Magnetic-core memory is one of the most significant breakthroughs in early computing history. While no longer used in modern systems, this technology laid the foundation for the reliable, durable memory that today’s automation, industrial controllers, and embedded systems depend on. Understanding magnetic-core memory is essential for engineers who want to appreciate how today’s RAM and non-volatile memory technologies evolved—and how memory reliability principles still influence industrial system design in Malaysia.

What is the Magnetic-Core Memory?

Magnetic-core memory is a form of early computer memory that stores data using tiny magnetic rings made from ferrite material. Each ring, known as a “core,” represents a single bit of information depending on its magnetic direction, clockwise representing a binary “1” and counterclockwise representing a “0.”

The technology’s durability, predictable performance, and immunity to electrical noise contributed significantly to its adoption in industrial environments long before PLCs and microcontrollers became widespread.

What is the Magnetic-Core Memory?

How Magnetic-Core Memory Works

Magnetic-core memory operates by storing information using magnetic hysteresis—the ability of a magnetic material to retain its magnetization after the magnetizing force is removed. In simple terms, once the core is magnetized in a particular direction, it stays that way until intentionally changed.

- Binary storage through polarity: Each ferrite core holds either a clockwise or counterclockwise magnetic orientation, representing a digital 1 or 0.

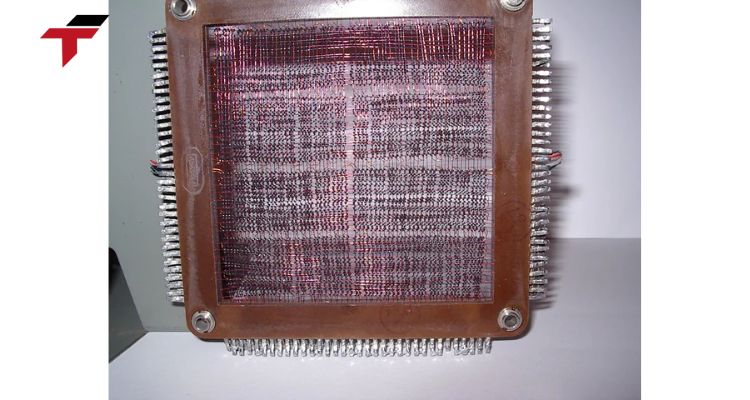

- Wires arranged in X-Y grids: Each core sits at the intersection of horizontal and vertical wires. Current sent through both wires selectively flips the magnetic state of a chosen core.

- The “Read and Rewrite” process: Reading a bit destroys its stored value, so the memory automatically re-writes it afterward, a unique characteristic of core memory.

- Non-volatile retention: The magnetic direction remains stable without electrical power, making the memory highly reliable in unstable environments.

- Immunity to electrical interference: Ferrite material is resistant to noise, which contributed to its suitability in early industrial automation hardware.

This mechanism allowed early computers and controllers to achieve unprecedented reliability, especially when operating in harsh or high-vibration environments.

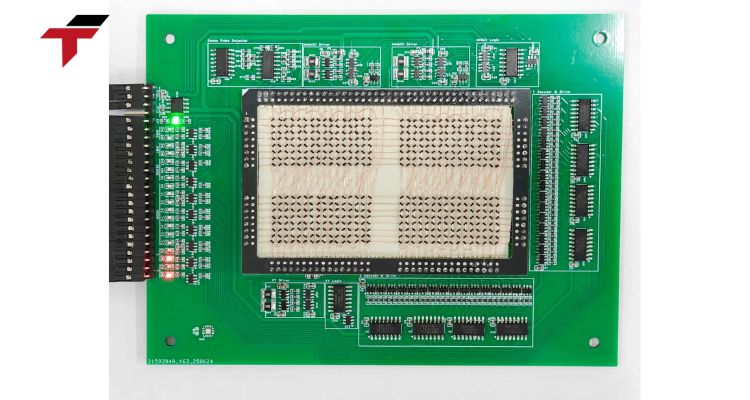

Technical Structure and Components

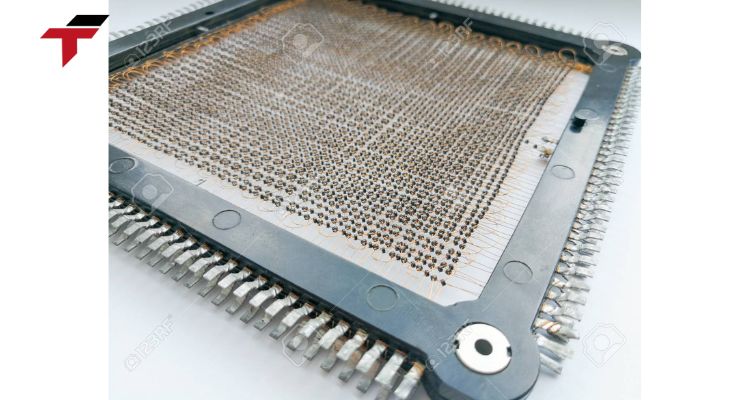

Magnetic-core memory consists of an intricate grid of wired ferrite rings arranged in planes. Each component plays a specific role in selecting, flipping, or detecting the magnetic state of the cores.

- Ferrite cores: Tiny donut-shaped magnetic rings, typically 1 mm or smaller, that store one bit each.

- X (horizontal) drive lines: Carry electrical pulses that activate one axis of the grid.

- Y (vertical) drive lines: Work with X lines to target specific cores for reading or writing.

- Sense line: A wire running diagonally through the core array to detect induced voltage when a core flips its magnetic state.

- Inhibit line: Controls whether a bit should be stored as 1 or 0 during the write cycle.

- Memory planes: Layers of these grids stacked together, increasing overall memory capacity.

This architecture made it possible to build memory systems with thousands or millions of bits—a monumental breakthrough at a time when electronic components were still evolving.

Technical Structure and Components

Magnetic-Core Memory vs Modern RAM

While magnetic-core memory was a transformative invention, it has long been replaced by semiconductor RAM. However, comparing the two technologies provides clear insights into the evolution of memory reliability, speed, and scale.

Before diving into the table, it’s important to understand that magnetic-core memory was groundbreaking for its non-volatility and ruggedness, but semiconductor RAM surpassed it with superior speed, energy efficiency, and scalability—critical factors for modern automation systems in Malaysia.

| Feature | Magnetic-Core Memory | Modern RAM (DRAM/SRAM) |

| Primary Material | Ferrite magnetic rings | Silicon-based integrated circuits |

| Volatility | Non-volatile | Volatile (data lost without power) |

| Speed | Slow (1–10 µs access time) | Extremely fast (nanosecond-level) |

| Durability | Very high; resistant to noise and environmental effects | Moderately high; sensitive to temperature & surges |

| Density | Low | Very high (gigabytes per module) |

| Cost | Expensive due to manual assembly | Mass-produced and affordable |

| Common Use Era | 1950s–1970s | 1980s–today |

| Industrial Application | Legacy controllers and early computers | Modern PLCs, HMIs, IPCs, robots, SCADA servers |

Relevance to Automation and Industrial Systems

Even though magnetic-core memory is no longer used in modern automation hardware, its design principles influenced the robust memory systems essential to today’s PLCs, SCADA servers, industrial PCs, and embedded controllers.

- Non-volatile memory concept: The idea of retaining data without power is foundational to modern EEPROM, flash memory, industrial SSDs, and PLC backup memory.

- Durability in harsh environments: Core memory’s resilience inspired rugged industrial storage solutions widely used in Malaysian factories exposed to heat, dust, vibration, or power instability.

- Legacy equipment understanding: Some older CNC machines and early industrial computers still reference memory architectures influenced by core memory designs.

- Industrial reliability design: The hysteresis principle remains crucial in designing reliable magnetic sensors, encoders, inductive components, and motor control systems.

- Educational value for automation learners: Understanding the evolution of memory helps new engineers grasp how modern control systems became faster, smaller, and more efficient.

By connecting legacy technology to modern industrial systems, readers gain a deeper appreciation of how far automation memory has evolved.

Relevance to Automation and Industrial Systems

Conclusion

Magnetic-core memory may no longer be used in modern industrial automation, but its legacy remains deeply embedded in the design philosophies that govern today’s memory systems. Its durability, non-volatility, and predictable performance made it a cornerstone of early computing and industrial control. As automation systems in Malaysia grow more advanced, driven by smart factories, IIoT, and high-speed industrial networks, the foundational ideas behind magnetic-core memory continue to influence how engineers think about reliability, data retention, and system stability.

Understanding this historic technology not only enriches your technical knowledge but also highlights how past innovations have shaped the memory solutions powering Malaysia’s modern automation landscape.